Lecture Exhorts Graduate Students to be Ambassadors

By Catherine Elvy, Staff Writer Science is hyped as the definitive authority for modern society, leaving many secular researchers with the potential for greater platforms – and more credibility – than their pastoral counterparts.

Science is hyped as the definitive authority for modern society, leaving many secular researchers with the potential for greater platforms – and more credibility – than their pastoral counterparts.As such, Christians who labor in scientific fields need to pause to consider the spiritual and cultural responsibilities tied to their roles as ambassadors for Christ.

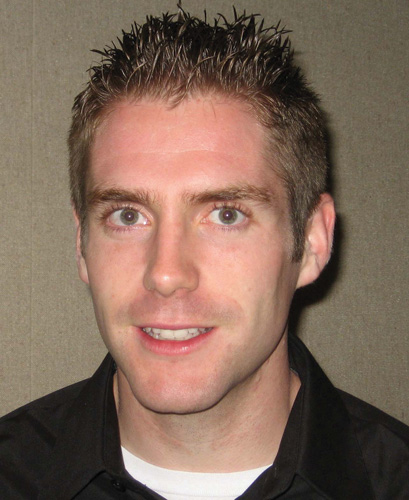

That was one of the themes from Matt Farrar when the post-doctoral associate in Cornell University's neurobiology and behavior department spoke on campus at a lecture hosted by the Graduate at Christian Fellowship Roundtable and the Chesterton House.

Farrar, Cornell Ph.D. '12, appeared at The Big Red Barn Graduate and Professional Student Center on April 12 to deliver a presentation entitled "Regnant Priests of a Neo-Orthodoxy: Science, Faith and Authority in the 21st Century." Farrar, a physicist who focuses on the development of nonlinear optical tools in studies of spinal cord injuries, based his presentation upon the writings of a series of Christian scholars, including Mark Noll, a historian who specializes in Christianity.

Farrar noted that many leading voices in Western Society question whether religion is a valid source of knowledge. And this perception is at the core of the issue for believers who work in secular fields.

"If knowledge of God no longer counts, what does count for knowledge?" Farrar asked rhetorically. Taking his concerns a step further, Farrar also rhetorically questioned whether Christianity should be cast aside to the realm of astrology, witchcraft, and mythology.

As for the scientific arena, the field is highly revered and features formidable barriers to entry – making practitioners, in effect, the modern clerics of the secular world. As well, much of what the public knows about science originates from "received tradition," and even fellow scientists have limited abilities to test claims, access complete texts of scholarly articles, and fully understand highly specialized research.

"We accept a lot because we receive it," said Farrar.

Glancing through history, Christianity has fallen from a place of

esteem – and source of legitimate knowledge, according to Farrar – because of wars and political conflicts carried out under the banners of religious motivation. Other sources of reputational damage stem from clashes between religion and science dating back to the so-called Galileo affair and from the marked separation of church and state within the constitutional framework of the United States.

The upshot is the undermining of the value of Christianity in governance and as a worldview.

On a positive trend, younger scientists appear less likely to be identified as atheists than their older counterparts, an observation echoed by some Christians in academia.

"That has been my sense for many years," said Karl Johnson, Cornell '89, Ph.D. '11, founding director of the Chesterton House.

"The militant secularism in the academy peaked more than a decade ago," Johnson said. Younger scientists are "a little more open to the possibility of religious beliefs" offering some benefits.

Also impacting the intersection of faith and scholarship, some Western churches have shifted from pursuing seminary-trained pastors to instead embracing preachers trumpeted for their energy, magnetism, and communication skills.

"You see a shift from moral knowledge to charismatic authority," said Farrar. "Historically, pastors were educated experts on matters vital to the world."

As for believers who labor in the sciences, Farrar strongly encouraged them to relish their worldly platforms and professional esteem.

"Develop a thoroughly informed faith that is congruous with your level of education," Farrar said. "You're going to be someone's professor, coworker..."

Farrar, who will join the faculty of Messiah College in fall 2015, urged Cornell graduate students to peruse materials related to faith in their chosen fields and to investigate voraciously key apologetics.

"Hold knowledge not just as a weekend hobby," he said.

Likewise, "support and encourage pastors.... Encourage them to share their knowledge," Farrar said.

Ultimately, scientists who are believers should embrace their roles as spiritual ambassadors, even within the rigorous world of scientific inquiry.

Farrar said he sides with St. Thomas Aquinas, the philosopher priest who embraced the existence of God as a self-evident truth. With that comes a call for like-minded believers to decide how to shape the culture of their professional spheres.

"Christians in the sciences have a vital part to play in presenting Christianity as a true body of knowledge," said Farrar.