Jonathan Edwards' Devotion to Bible Study

By Catherine Elvy, Staff Writer

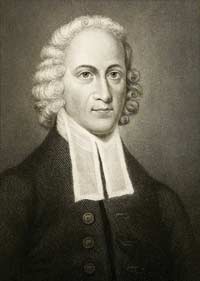

An article in the latest issue of Jonathan Edwards Studies paused to shed light on the everyday habits and intense biblical study of the famed revivalist preacher and early Yale University alumnus.Jonathan Edwards stands as one of the top figures in the spiritual history of the United States, and his life serves as an inspiration to believers across the globe.

An article in the latest issue of Jonathan Edwards Studies paused to shed light on the everyday habits and intense biblical study of the famed revivalist preacher and early Yale University alumnus.Jonathan Edwards stands as one of the top figures in the spiritual history of the United States, and his life serves as an inspiration to believers across the globe.In the piece, Douglas Sweeney, a key Edwards' scholar with ties to Yale, reflected on the scriptural fervor behind the theologian's scholarship. Sweeney serves on the editorial board for the online journal, part of the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale.

"Edwards devoted most of his waking life to studying the Bible, its extra-biblical contexts, its theological meanings, and its importance for everyday religion," wrote Sweeney, the director of the Jonathan Edwards Center at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Illinois.

Sweeney, a former lecturer in Yale's Divinity School and former assistant editor of Yale's The Works of Jonathan Edwards, also was a featured speaker in late February at a conference on Edwards at Durham University in the United Kingdom.

Edwards, a key figure of the Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s, is best known for his sermon entitled Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God. The Yale alumnus of 1720 and 1723 also served as a president of Princeton University.

As a result of Edwards' passion for spiritual contemplation, the colonial figure arose most mornings in the predawn hours and often studied 13 hours per day, Sweeney wrote, citing historical sources.

Likewise, Edwards' diary suggested he often skipped dinner, rather than permit interruption to Bible study.

Indeed, Edwards, who entered Yale just shy of 13, vowed as a youth to "study the Scriptures so steadily, constantly, and frequently, as that I may find, and plainly perceive myself to grow in the knowledge of the same," Sweeney noted, quoting from the Puritan's writings.

Edwards' commitment spilled over from the pulpit, and he told congregants that religious study was for all and certainly not limited to clergymen. He even recommended colonists dedicate as much of their time to seeking God as pursuing "mammon."

Additionally, Edwards was shaped by living during an era when most of his close associates would have identified the Bible as their most important book, a frequent source of inspiration and insight.

"The Bible is full of wonderful things," Edwards told parishioners, adding it also is "unerring" and a "precious treasure." As well, he asserted the knowledge contained in the Scriptures is "infinitely more useful and important" than the knowledge of other sciences, Sweeney noted, citing from records.

Not surprisingly, the words of the Bible played a central role in New England's colonies, which derived laws and morals from its contents.

As well, the Scriptures were at the forefront of worship services in the Puritanical enclaves. The Puritans dubbed their churches as "meeting houses" and they shunned stained-glass windows and other fixtures that might distract congregants from the sacred texts. Some houses of worship sang a cappella and even forbade the use of musical instruments, Sweeney wrote.

Similarly, many Puritans embraced literacy, and most children were taught to read with the Bible. Small towns hired reading teachers, and larger boroughs built primary schools. Residents expected their clergy to deliver meaty, insightful messages, Sweeney said.

Edwards learned Greek and Hebrew as a boy with his father, who ran a grammar school in the parlor of their parsonage. He tested in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew when matriculating at Yale and utilized those languages throughout his college career, Sweeney wrote.

Today, 300-plus years after his birth and a half century into the so-called Edwards' Renaissance, few scholars have thoroughly examined the minister's "massive exegetical corpus" taken from his decades of intense study.

But, ironically, Edwards' theology has "far more adherents during the past 200 years than it ever possessed in colonial British North America," Sweeney wrote.

As for Edwards, the Bible's subjects were simply inexhaustible, reflecting an infinite, glorious God, and Edwards embraced a lifelong love affair with the Scriptures.