A Christian Union: The Magazine Interview

Christian Union: The Magazine recently interviewed Dr. Doug Sweeney about the life and long-lasting impact of David Brainerd, a missionary to Native Americans during the 18th century. Sweeney is Professor of Church History and the History of Christian Thought, Chair of the Department, and Director of the Jonathan Edwards Center at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. He has been published widely on Jonathan Edwards, early modern Protestant thought, and the history of evangelicalism. His books include two volumes in the Yale Edition of The Works of Jonathan Edwards (Yale, 1999, 2004); Nathaniel Taylor, New Haven Theology, and the Legacy of Jonathan Edwards (Oxford, 2003); and Edwards the Exegete: Biblical Interpretation and Anglo-Protestant Culture on the Edge of the Enlightenment (Oxford, 2016).

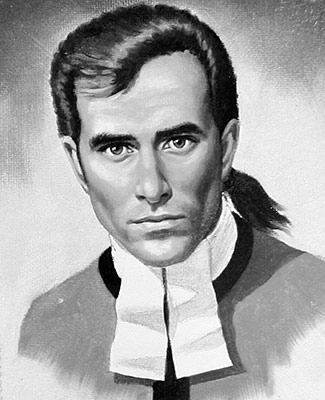

In 2015, Sweeney and other theologians were interviewed for Church Works Media's DVD, The Life of David Brainerd, A Documentary. Although he died at 29, Brainerd's passion for the Lord and lost souls inspired generations of missionaries, especially after Edwards published his biography, An Account of the Life of the Late Reverend Mr. David Brainerd. His legacy was also recognized by Yale—despite being expelled, the university later named a building after him, Brainerd Hall at Yale Divinity School.

CU Magazine: What were the circumstances that led to David Brainerd's expulsion from Yale in 1741?

Doug Sweeney: Brainerd was 21 when he began to study at Yale, several years older than most freshmen in his day, all of whom were required to defer to upper classmen, no matter what their age. He had just been converted and was an immature Christian who struggled with pride amid the spiritual excitement of New England's Great Awakening.

Doug Sweeney: Brainerd was 21 when he began to study at Yale, several years older than most freshmen in his day, all of whom were required to defer to upper classmen, no matter what their age. He had just been converted and was an immature Christian who struggled with pride amid the spiritual excitement of New England's Great Awakening.Worried about the potential for spiritual arrogance among students taken by the revivals, Yale's leaders passed a rule in September 1740, requiring that if "any Student of this College shall directly or indirectly say, that the Rector, either of the Trustees or Tutors are Hypocrites, carnall or unconverted Men, he shall for the first offence make a publick confession in the Hall, and for the Second Offence be expelled."

Sometime during the fall of 1741 (we're not exactly sure when), Brainerd stayed in the chapel with some friends after a service in which their tutor, Chauncey Whittlesey, had offered a tepid prayer. "He has no more grace than this chair," Brainerd complained about Whittlesey. A freshman overheard him and told a woman living nearby, who reported the incident to Yale's Thomas Clap, then rector of the College. Clap demanded that Brainerd make a "public confession, and . . . humble himself before the whole college." Brainerd refused—an act for which he later repented to Clap and others—and thus was kicked out of Yale.

CU: How did this expulsion impact his ministry?

DS: His expulsion made it difficult for Brainerd to prepare for and function as a standing order minister in Connecticut. In April 1742, he moved to Ripton, Connecticut and studied for the ministry with Jedediah Mills, a pro-revival pastor. In July of that year, he earned a license to preach from the Fairfield East Ministerial Association, a largely evangelical body. But Brainerd had been branded as a spiritual trouble maker.

As the revivals continued, Brainerd also grew concerned about the plight of Native Americans. So as his prospects for regular pastoral ministry declined, he began to contemplate the possibility of ministry to Native Americans living west of the Hudson. In November 1742, he was appointed as a missionary by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge. In March 1743, he trained as a missionary in Stockbridge, Massachusetts with the Rev. John Sergeant, who ran a mission there (the one Jonathan Edwards later served). And in April 1743, he traveled to New York to serve the Native Americans at Kaunaumeek. From May 1744 through 1746, he served the Delawares (Leni Lenape) of eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey. He was ordained for this work by the New York Presbytery in June 1744 (finding clerical redemption among friendly Presbyterians), but his life had been forever transformed by his expulsion.

CU: What were the implications for future Ivy League colleges, Princeton and Dartmouth?

DS: Princeton was founded as a New Side (i.e. pro-revival, or evangelical) Presbyterian school in 1746, while Brainerd was at work among New Jersey Delawares. Before Nassau Hall was raised in 1756, classes met in the homes of Princeton's presidents. The Rev. Jonathan Dickinson, Princeton's first president, served a Presbyterian church in Elizabeth, New Jersey (called Elizabethtown back then, in the era when Princeton was called the College of New Jersey). Inasmuch as Brainerd lived in Dickinson's home during the winter of 1746/47 (suffering from the illness that would kill him soon thereafter, we think tuberculosis), Brainerd participated in the launch of Princeton. More importantly, perhaps, by the mid-1740s, Yale's leaders had grown suspicious of evangelicals like Brainerd and Princeton had come to be a better fit for them.

Dartmouth was established long after Brainerd died, in 1769, by Eleazar Wheelock. But Wheelock had been a friend and admirer of Brainerd, inspired by his example to serve the Iroquois people. In 1748, a year after Brainerd died, Wheelock opened a boarding school for both Iroquois and Anglos in Lebanon, Connecticut, later moving it to Hanover, New Hampshire, Dartmouth's home. The Rev. Samson Occom, one of Wheelock's first converts, helped Wheelock raise money for this missionary venture, spending over a year in Britain preaching sermons for the cause (1766-67), raising money for the college from King George III himself. Occom later felt betrayed when Wheelock used these funds more for Anglos than Native Americans, who would never constitute a high percentage of Dartmouth students. Nevertheless, Dartmouth emerged from early evangelical missions—and went on to boast more Native American alumni than all other Ivy League institutions combined (nearly 1,000).

CU: Why did Brainerd possess such a passion for Native Americans and those that didn't know Christ?

DS: His life had been transformed by the power of the Gospel. He had been changed from an arrogant evangelical adolescent to a humble servant of Christ, full of love for God and neighbor. His experience had taught him what the love of God can do when it fills someone's life, and he longed to share that love with those around him.

One of my favorite sections in Brainerd's diary testifies to this. He wrote it on April 19, 1742:

In the forenoon, I felt a power of intercession for precious immortal souls, for the advancement of the kingdom of my dear Lord and Saviour in the world; and withal, a most sweet resignation, and even consolation and joy in the thoughts of suffering hardships, distresses, and even death itself, in the promotion of it . . . . God enabled me so to agonize in prayer that I was quite wet with sweat, though in the shade, and the wind cool. My soul was drawn out very much for the world; I grasped for multitudes of souls. . . . I enjoyed great sweetness in communion with my dear Saviour. I think I never in my life felt such an entire weanedness from this world, and so much resigned to God in everything. Oh, that I may always live to and upon my blessed God!

Brainerd's diary is full of such raw spirituality.

CU: Despite failing health and terrible conditions, what kept Brainerd strong in faith?

DS: After God changed his life, Brainerd's hunger for intimacy with God grew so strong that it distracted him from caring for his body. Here's another typical passage from his diary, penned November 4, 1742:

But of late, God has been pleased to keep my soul hungry, almost continually; so that I have been filled with a kind of a pleasing pain: When I really enjoy God, I feel my desires of him the more insatiable, and my thirsting after holiness the more unquenchable; and the Lord will not allow me to feel as though I were fully supplied and satisfied, but keeps me still reaching forward; and I feel barren and empty, as though I could not live without more of God in me . . . Oh, that I may feel this continual hunger, and not be retarded, but rather animated . . . to reach forward in the narrow way, for the full enjoyment and possession of the heavenly inheritance. Oh, that I may never loiter in my heavenly journey!

His spiritual appetite simply outstripped his instinct for self-preservation—for better and for worse.

CU: What was the relationship and commonalities between Edwards and Brainerd?

DS: Edwards spent much of his ministry trying to help people understand the difference that the Holy Spirit makes in one's life when one is truly close to God. Sometimes, he did this with teaching from the Bible. At other times, though, he preferred to use everyday Christians as examples. He used his own wife Sarah as an example of God's love at work in ordinary people. He used several others, too. But the example over whom he spilled the most ink was Brainerd.

Partly due to his pride as a young man at Yale, Brainerd served Edwards well as an example of transformation by the power of the Spirit. And partly because of his reckless abandon as a missionary—living alone in the wilderness, with little food or shelter—he served as an example of what it means to bear the cross and follow Christ through death to resurrection.

So Edwards and Brainerd shared the same priorities. But Brainerd also lived in Edwards' house at the very end of his life (for about five months). He and the family grew close. As they did, Brainerd inspired them with his faith. Edwards wrote in his Life of Brainerd,

But now I had opportunity for a more full acquaintance with him [as he lived and died in Edwards' house]. . . We enjoyed not only the benefit of his conversation, but had the comfort and advantage of hearing him pray in the family, from time to time. His manner of praying was very agreeable; most becoming a worm of the dust, and a disciple of Christ, addressing to an infinitely great and holy God, and Father of mercies; not with florid expressions, or a studied eloquence; . . . at the greatest distance from any appearance of ostentation, and from everything that might look as though he meant to recommend himself to those that were about him, or set himself off to their acceptance; free too from vain repetitions, without impertinent excursions, or needless multiplying of words. He expressed himself with the strictest propriety, with weight, and pungency; and yet what his lips uttered seemed to flow from the fullness of his heart, as deeply impressed with a great and solemn sense of our necessities, unworthiness, and dependence, and of God's infinite greatness, excellency, and sufficiency, rather than merely from a warm and fruitful brain, pouring out good expressions. . . In his prayers, he insisted much on the prosperity of Zion, the advancement of Christ's kingdom in the world, and the flourishing and propagation of religion among the Indians. And he generally made it one petition in his prayer, that we might not outlive our usefulness.

I have long been fascinated with passages like this. They say a lot, I think, about what a public religious figure like Edwards found attractive in Brainerd.

CU: Why has Edwards' book, The Life of David Brainerd, impacted so many for such a long period?

DS: It's hard to communicate this to those who've not read the book, but Brainerd's commitment to the love of God and neighbor is astounding and inspiring. Even when readers have decided that they disagree with Brainerd, or have wished that Brainerd would have taken better care of himself (both physically and emotionally), they have usually concluded that they want to be more like him in his willingness to sacrifice his own creature comforts for the sake of other people.

Thoughtful, sensitive readers who get dispirited by the glib faith of self-confident Christians also cheer Brainerd's honesty about his shortcomings and insecurities. The apostle Paul emphasized that "God has chosen the foolish things of the world to shame the wise, and God has chosen the weak things of the world to shame the things which are strong, and the base things of the world and the despised, God has chosen, the things that are not, that He might nullify the things that are, that no one should boast before God" (I Corinthians 1:27-29). Brainerd's c.v. shows this message to be true. He was a privileged man, a prodigy, who learned this lesson the hard way, an Ivy League student who died to self and found everlasting love in Jesus Christ. Despite his flaws, he joined the ranks of those of whom the writer of Hebrews said "the world was not worthy" (Hebrews 11:38). Kindred spirits still thrill to his story today.