by Titus Willis

Originally posted October 8, 2017, in Columbia Crown & Cross. Posted here with permission of the author.

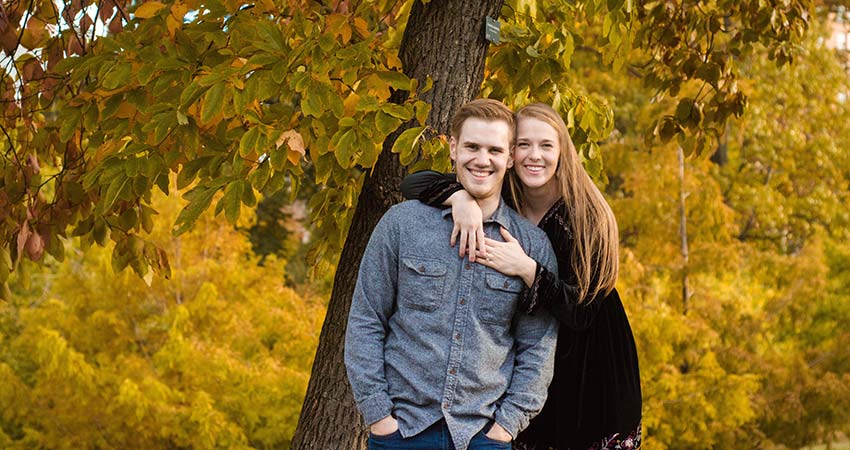

Six weeks ago, with a secret photographer looking on, I escorted my girlfriend Taylor to a patio overlooking a lake upstate. Taylor and I had met here at Columbia through mutual friends, sat beside each other in Art Hum, and went on a dozen dates in the city. Just before the outset of our senior year, right there on that patio, I proposed to her; she said yes, with the camera bulb flashing behind her.

Needless to say, Taylor and I have taken a few deviations from the common college dating route. When we get married next summer, we will both be 22 years old, a half-decade younger than the national average age of first marriage and perhaps a decade younger than the average Columbia student’s. We aren’t sexually active, which frequently surprises people. We read a devotional book and pray together to promote intimacy in our emotional and spiritual lives. Talk to someone who knows us well and they might mention that we’ve become abstinence-minded matchmakers for others—it’s easy to fix up potential couples since we only know a handful of Columbia undergrads who approach romantic relationships like we do. But as our model, which draws a great deal from the doctrines of Christianity, has worked for us, we believe it could work for everyone, regardless of religious conviction.

What exactly does our dating model entail that makes it so rare on a college campus? The model, as I will define it here, has three distinct characteristics, all of which have significant (but not exclusive) links to Christian literature and Evangelical tradition. First, our model is solely concerned with serious relationships: since marriage is the true endgame, making the decision to pursue someone should only occur if a lifelong commitment is in play. Second, our model encourages young men and women to focus primarily on their partners’ emotional needs. For us, this philosophy comes from the Bible, but it ought to fall more largely under the common code of human kindness. According to the book of Ephesians, husbands are to love their wives with reckless abandon and wives are to trust their husbands’ loving wisdom when inevitable problems arise, but boyfriends and girlfriends of all faiths should work on their emotional compatibility with this kind of seriousness. Third—and this is what makes it most countercultural—our model implores young couples to abstain from sex until the marriage vows are exchanged. “Flee from sexual immorality,” the Bible says. “Let the marriage-bed be undefiled.” However, this approach also need not be biblical. That pre-marital abstinence runs so contrary to the mainstream is a fact we will return to later.

The countercultural reality of our model has been made especially clear to me since I proposed to my now-fiancée. Most people at Columbia express confusion, disbelief, or even concern when they hear about the aforementioned details of our relationship. We’re such a rare breed that, according to a reputable source, the Columbia Daily Spectator might write a story about us. On a campus where every Resident Adviser is encouraged to hand out free condoms and conversations during first-year orientation detail the glories of casual hookups, these reactions are not surprising.

Indeed, the larger culture has grown more and more supportive of looser relational boundaries. A 2016 study promoted by USA Today, for example, shows that millennials are 48% more likely than previous generations to have sex before a first date. One of the researchers claims that our generation, with its career-oriented, ad hoc attitude, tends to treat sex as a “relationship interview”—that is, what first dates are supposed to be for. But no one really needed a study to know that relationships are growing more casual and more sexualized: watch a television show from the ‘70s like the network comedy Three’s Company, sharply criticized in its time for its morality, and compare it to Parenthood, a critically-acclaimed, family-oriented 2010s NBC show that treats casual dating and loose sexual boundaries as the norm even for old-fashioned grandparents. While we may quibble on the merits of a society that has grown fonder of relationships that are low on commitment and high on sexual intimacy, the advent of that society is undeniable.

Misconceptions and ill-informed opinions abound with respect to our dating model, especially on the topic of saving sex for marriage. “[Some] Americans value chastity in a way I find silly, problematic, and, ultimately, counterproductive,” journalist and nationally-syndicated radio host Bomani Jones once wrote. Others have posited that such serious relationships are bad for young women because of patriarchal expectations that are often associated with marriage. To me, however, the saddest misconception I hear is that Taylor and I are approaching our relationship this way only because of our religious beliefs. If it weren’t for our faith, people say, we would be sleeping together frequently, planning to move in together after college, and saving the lifelong marriage commitment for at least a half-dozen years.

Religion certainly is a factor in our decision to pursue this kind of relationship, but I would follow these relational guidelines even if I stopped following Jesus. After all, a dating model that prioritizes personal connection and potential marriage is conducive to social improvement. Per a recent doctoral survey, couples who wait to have sex until marriage get divorced at a 5% clip. This number is, of course, staggering; the national rate is 10 times higher. While each case is different, that vast discrepancy by-and-large means healthier marriages and children who are spared the emotional trauma that arises from their parents’ divorce. These basic results—fewer divorces and fewer children emotionally harmed by them—ultimately lead to a healthier society. Relational looseness, on the other hand, often fosters broken families and lasting residual feelings of heartbreak.

In short, couples who practice our model believe that sex is beautiful, precious, and devastatingly powerful; and that, like most beautiful, precious, and devastatingly powerful things, it belongs only in a very specific context. Taylor and I try to conserve our desires, even now as an engaged couple, because we instinctively realize that this unique human act of passion is not something we should share dispassionately. When approached casually, sex is thought to be sound and fury signifying nothing, putatively comparable to an animal in heat, but we all know from personal relationships around us that these experiences often come with unanticipated strings attached. So why build up any sort of emotionally-fraught physicality with someone you’re not planning to spend the rest of your life with? Is it really worth a few brief moments of pleasure to risk the emotional damage that could follow, not to mention the joy you could feel when experiencing every ounce of that pleasure with the person you marry?

Perhaps the more compelling claim against our model is a feminist one—many people believe that Christians hold retrograde beliefs on the roles of women in relationships, so such relationships are problematic to the cause of gender equality. Some might say that every relationship with gender roles (even ones as positive as those advocated in the book of Ephesians) is bad for women, but I disagree, so long as the women are actually choosing for themselves. From my experience both here at Columbia and through friends at other schools, I have observed that boyfriends who follow our dating model exert no pressure on the women they are dating to be submissive, and while empty-nest mothers and fathers are fond of jesting about future grandchildren, very few of them seriously challenge their daughters to get married or to subjugate their career aspirations for their husbands. Any person who makes decisions for a romantic partner against their will is not following Ephesians, and is certainly not following our model. Relationships that follow our dating model should be constantly balanced and completely consensual; though I may get my way instead of Taylor at one moment, she will get her way over me in another, and neither of us has a clear upper hand.

Furthermore, if our model is bad for women, feminists should fight for the complete abolition of dating in general, because no other dating model is better for women. Washington Post contributor Russell Moore explains the dangers of an “empowering” dating culture in his 2016 book Onward:

Despite the promise of women’s empowerment, the Sexual Revolution has given us the reverse. Is it really an advance for women that the average adolescent male has seen a kaleidoscope of images of women sexually exploited and humiliated in pornography? … These things empower men to pursue a Darwinian fantasy of the predatory alpha-male in search of nothing but power, prestige, and the next orgasm. That’s not exactly a revolution. (176-77)

The truth of the matter is that women deserve to freely elect how they wish to live their romantic lives—anything short of this is a subversion of our plural society. Television writers, college administrators, and cultural trendsetters who glorify casual dating without paying attention to its flaws are making a great mistake, one that has led to far too many non-consenting women being objectified, manipulated, and traumatized by people who are actively ignorant of their wants and needs. No wonder advocates of our model in the Christian world wage wars on pornography and sexual gluttony, the kind so-called icons like Hugh Hefner made a life espousing. Perhaps the mainstream, if they really do want to promulgate feminism and extinguish rape culture, ought to pay attention.

Despite the cultural mores, Taylor and I have found love actualized on Columbia’s campus. Now ten months away from tying the knot, we will have to balance wedding-planning with coursework and graduate school applications for the rest of the academic year. Some may consider this a stressful workload, but I consider myself incredibly fortunate to be spending my senior year this way. A person’s twenties are often mired in uncertainty—there are job interviews to master, rent payments to make, and, in some cases, relationships to define; scrolling through social media, watching television, or chatting with a friend can remind you just how exhausting it can be to have a love life in limbo. Not for us. My fiancée and I found serious dating that works, and we would like nothing better than for others to adopt the model we have enjoyed working through together.

Titus Willis (CC ’18) is the Editor-in-Chief of Columbia Crown & Cross. He loves the Lord, his fiancée, and, unfortunately, the New York Mets.