Seeking a Christ-Awakening

Editor’s note: The following article, by David Bryant, was originally posted in 2021 and is adapted from his essay in the 2004 updated edition of Jonathan Edwards’ influential book on prayer. It was marked by a thirty-six word title that began with three famous words: An Humble Attempt. The modern version’s title is “A Call to United, Extraordinary Prayer…An Humble Attempt.”

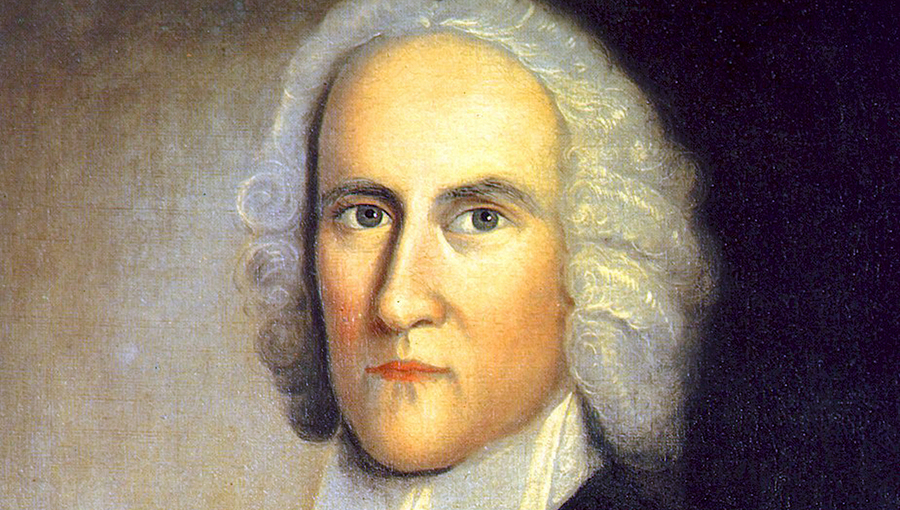

Like waves of incense, over the past forty years prayer for revival (or as many often call it, a “Christ Awakening”) has ascended across America in ways never experienced before. Often these gatherings are called “Concerts of Prayer,” a term taken from a book on prayer by one of our nation’s greatest spiritual leaders, Jonathan Edwards.

But interestingly, this book was really not about prayer. Edwards (Yale, Class of 1720) knew the true secret to igniting and sustaining a work of prayer—individually or unitedly—was to make much of the greatness of Christ. Prayer was the means to the end of a fuller awakening to the wonders of Christ for ALL He is today.

Nothing could be more relevant to where we Jesus followers find ourselves in this critical hour.

Here’s the backstory: Initially, Edward’s treatise on prayer, An Humble Attempt, had a practical mission. It was his response to a document from Scottish pastors called a Memorial.

Memorial rose out of scores of prayer societies already functioning in Scotland around 1740, especially among young people. By 1744, a committee of ministers determined it was time to do more. They decided to try a two-year “experiment,” uniting all prayer groups and praying Christians in their nation into a common prayer strategy. They called for focused revival prayer on every Saturday evening and Sunday morning, as well as on the first Tuesday of each quarter.

By 1746, these Scottish intercessors were so gratified by the impact of their experiment that they composed a call to prayer to the church worldwide, especially in the colonies. However, this time the “concert of prayer” was to be for seven years!

Five hundred copies of Memorial were sent to Boston for distribution. One fell in Edwards’ hands, who at the time was the pastor of the second largest congregation in all of New England.

Initially he was attracted to it, he says, because it was anonymous – none of the ministers promoted themselves in the effort. He was also taken with their methodology, with its potential for mobilization, and its inherent value for holding Christians accountable to the work of prayer.

Edwards mentions all of this in the opening pages of An Humble Attempt. But Edwards also felt he could assist the initiative by providing additional theological foundations for the Memorial’s vision and by answering a variety of objections he was sure it would face. No one else was better qualified to do so.

What Was Edwards Trying to Say?

In 1712, when British Christians called for intensified prayer for a Protestant, not Catholic, king to succeed Queen Anne, their foundational text was Zechariah 8:20-22.

Edwards returned to this passage to anchor his endorsement of a Concert of Prayer. And for good reason. It underscored, as well as any other biblical text, the attitude, agenda, impact, and ignition of any prayer movement. Despite where one might place the passage on an eschatological timetable, in principle it describes exactly what Edwards knew it would take to sustain and quicken the fruits of the Great Awakening.

What is so amazing is that over the past two hundred and fifty years, the church has experienced “intermediate fulfillments” of Zechariah 8, just as Edwards predicted we would: There shall be given much of a spirit of prayer to God’s people, in many places, disposing them to come into an express agreement, unitedly to pray to God in an extraordinary manner, that he would appear for the help of his church, and in mercy to mankind, and pour out his Spirit, revive his work, and advance his spiritual kingdom in the world, as he has promised.

This disposition to prayer, and union in it, will gradually spread more and more, and increase to greater degrees; with which at length will gradually be introduced a revival of religion and disposition to greater engagedness in the worship and service of God, amongst his professing people... In this manner religion shall be propagated, till the awakening reaches those that are in the highest stations, and till whole nations be awakened.

Towards this vision, An Humble Attempt breaks into four major sections: Part I: Response to the Memorial itself; Part II: Discussion of promises for latter-day glory; Part III: Review of motives for united prayer; and Part IV: Answering objections to the call to prayer.

Of all the contributions that the book makes to individual and corporate prayer life, however, nothing can surpass how Edwards built his strongest case based on the hope one is praying towards. He knew this to be the key for igniting and sustaining the work of prayer.

Without necessarily agreeing with his postmillennial eschatology, one cannot ignore his apologetic that “it is natural and reasonable to suppose, that the whole world should finally be given to Christ as one whose right it is to reign.” Thus, Christians must not permit themselves, pleads Edwards, ever to pray for less than this as the goal of all intercession, and of every single prayer. In fact, if we forego millennial discussions altogether for the moment, and simply concentrate on what might better be termed “the Consummation,” can any of us fail to embrace Edwards’ appeal to pray prayers wrapped up in the great hope before us, when he writes:

Such being the state of things in this future promised glorious day of the church’s prosperity, surely it is worth praying for. Nor is there any one thing whatsoever, if we view things aright, for which a regard to the glory of God, a concern for the kingdom and honour of our Redeemer, a love to his people, a pity to perishing sinners… would dispose us to be so much in prayer, as for the dawning of this happy day, and the accomplishment of this glorious event?

With such a comprehensive vision, Edwards argued that prayer for the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, with all the ramifications that biblical promises suggest, was by far the highest prayer agenda Christians could wage in this present age. In that direction, he urged, lies every reason to expect great success in any Concert of Prayer. As he concludes at one point:

For, undoubtedly, that which God abundantly makes the subject of his promises, God’s people should abundantly make the subject of their prayers. It also affords them the strongest assurances that their prayers shall be successful (italics his).

Among the motives for concerted prayer, Edwards reasoned quite clearly that unity in prayer is both God’s means to the Consummation, as well as an end in itself. In other words, although praying unitedly furthers Christ’s reign, it also forges the very result for which God calls us to be joined in prayer—to foster the visible unity that can convince the world Christ is who he says he is.

To that end, Edwards was open to all theological camps to come together–even those who opposed the Great Awakening–as long as their shared passion was for the advancement of Christ’s kingdom through all of Christ’s church in answer to our united prayers.

Interestingly, many of the objections Edwards anticipated I have watched surface repeatedly in modern prayer movements. That’s why his responses are so relevant for us. For example, he confronted charges that the Concert of Prayer was merely a form of superstition; or that it was an encouragement to pharisaicalism; or that it misrepresented God’s timing, making the effort premature and unnecessary; or simply that it revealed the predisposition of some towards novel, and dangerous, addition. There were extended sections where Edwards tried to answer various eschatological controversies that had the potential of derailing the movement.

Bottom line: An Humble Attempt warns us that mobilizing united, Christ-exalting prayer will come at a price.

Were Edwards’ Labors in Vain?

An Humble Attempt met with meager success in Edwards’ lifetime. Three years after he wrote it, he was dismissed from his church (over debates about administering the Lord’s Supper) and sent to a little congregation in Stockbridge, on the colonial frontier. Seven years later, trustees at Princeton University prevailed on him to take over its presidency, where he died five weeks after coming into office (due to complications from an experimental smallpox vaccination, taken to help scientists test it for use with the larger population).

Interestingly, in that same year (1757) a Concert of Prayer was raised up by Princeton students, and resurfaced repeatedly during the next one hundred years on that campus, resulting in multiple student awakenings.

However, it wasn’t until it was republished in England in 1789, that Edwards’ “attempt” began to bear real fruit. Embraced by the fledgling prayer movement across the land, and adopted and promoted by William Carey and his little prayer band in England, it eventually became a major manifesto for the Second Great Awakening.

Space does not allow a thorough report on how An Humble Attempt was reissued in subsequent generations, and the impact it had on other awakenings (including the Third, beginning around 1857–exactly one hundred years after Edwards’s death). This happened not only on the home fronts, however, but throughout many mission fields. For example, in 1897, upon returning from a nine-month trip to visit chapters of the Student Volunteer Movement for Foreign Missions in nearly forty nations, the general director, John R. Mott, made a curious notation in his journal. He wrote that the vitality of each chapter could only be explained “by the Concert of Prayer going on in each one.” From those student prayer initiatives came nearly 20,000 missionary recruits, with another 70,000 joining the Laymen’s Missionary Society to send them. Edwards’ vision was at the core of the focus, the commitment, the sacrifice, the harvest, and the intercession behind this unprecedented story in 2,000 years of missionary advance.

So how did Edwards handle heaven’s delays in his lifetime? When Edwards’ initial “attempt” seemed to stall, would he have been discouraged? As the years passed without another glorious visitation of Christ upon his church, would he have despaired over unanswered prayer? Seeing so little visible unity, or extraordinary praying, or passion for the Consummation, would he have been embittered in his last years?

Not if he heeded his own concluding words in An Humble Attempt. All of us would do well to listen to this man “abounding in hope by the power of the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 15:13). Reflecting, in his final paragraph, on what should happen if, at the close of the seven-year experiment, there would still be little change, he admonishes:

But let it be considered whether it will not be a poor business, if our faith and patience is so short-winded that we cannot be willing to wait upon God for seven years, in a way of taking this little pains, in seeking a mercy so infinitely vast. For my part, I sincerely wish and hope that there may not be an end of extraordinary united prayer, among God’s people, for the effusions of the blessed Spirit… and that extraordinary united prayer for such a mercy will be further propagated and extended…God has not said to the seed of Jacob, Seek ye me in vain… But whatever our hopes may be in this respect, we must be content to be ignorant of the times and seasons, which the Father hath put in his power; and must be willing that God should answer prayer, and fulfil his own glorious promises, in his own time.

For you see, as I said at the top, in the end this treatise is really not about prayer. Its major focus is on CHRIST. On the exaltation of Christ, the reign of Christ, the kingdom of Christ. It was about how our hope in Christ should drive us to “explicit agreement and visible union in extraordinary prayer for the revival of the church and the advancement of Christ’s kingdom on earth,” as Edward’s put it in the original title of the book.

Edwards knew that the ultimate answer to every prayer for revival (or to any other prayer, for that matter) was that the Father, by the Spirit, gives us more of the fullness of the Son—infuses us with a greater revelation of Christ, unleashing among us fresh, proactive triumphs of Christ—all of it beginning with the reintroduction of God’s people to the majesty and glory and supremacy of Christ.

Bottom line: It is the person of Christ that is the source, substance, and summit of all believing prayer. True revival is all about Christ.

Today across our nation, Edward’s vision is being restated as a humble attempt to foster and serve nationwide “Christ Awakening” movements (revival) in answer to over four, unparalleled decades of concerted prayer in our land for nothing less.

Have you become a part of it?

To learn more about Christian Union's ministry at some of the nation's most influential universities and its desire to foster national awakening, please click here.

David Bryant is often called the “father of the modern prayer movement,” David Bryant has been a pastor, minister-at-large for Intervarsity Christian Fellowship, founder of Concerts of Prayer International and chairman of America’s National Prayer Committee. Today, he leads Proclaim Hope!, a ministry designed “to foster and serve a nationwide Christ Awakening movement.” His books, podcast, resource materials, and video training (most of it offered for free) are available at ChristNow.com.